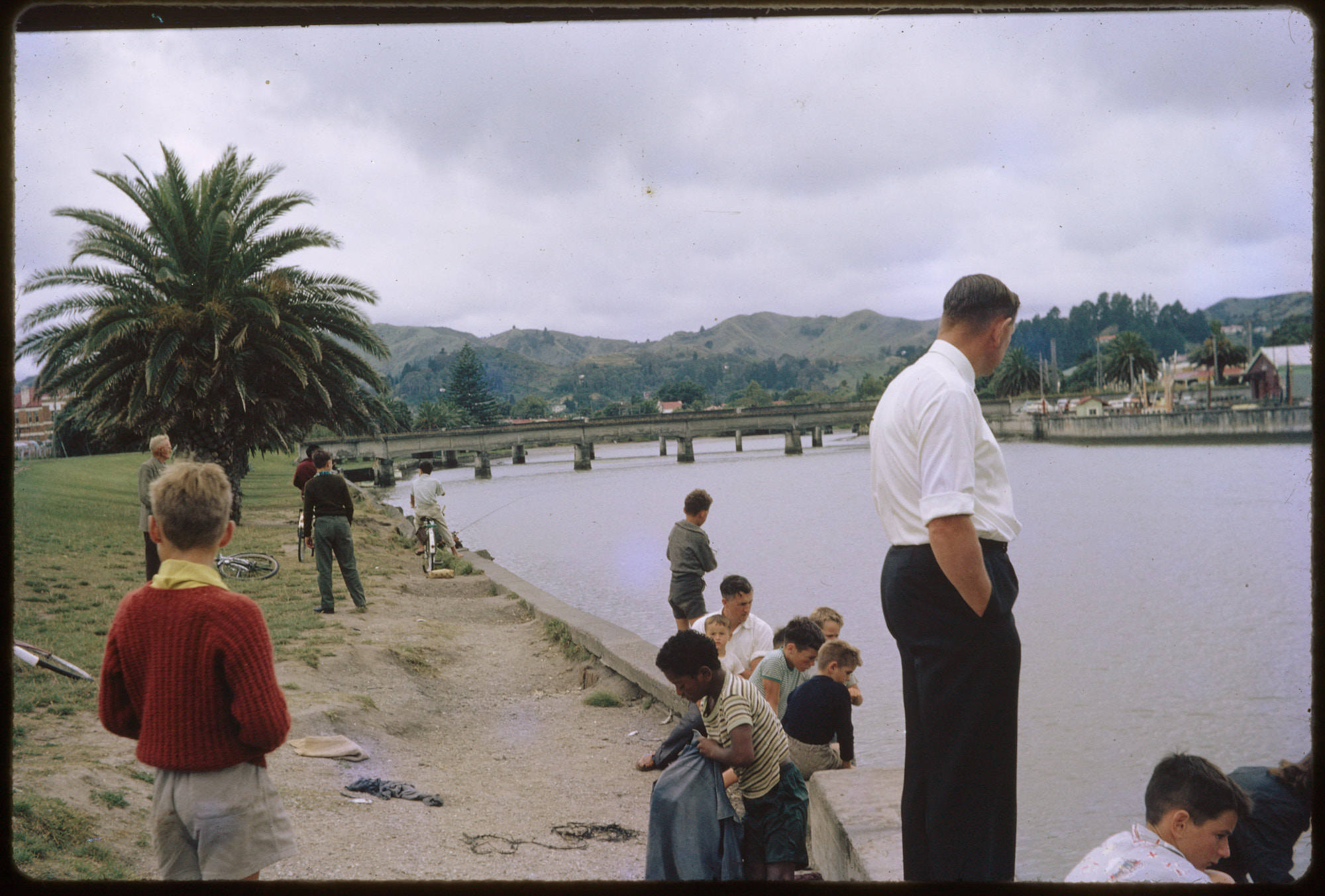

In the last post on the Arrowsmith Phoenix Palms (Part 3: Partial Removals in Hastings) we saw what happened to the Phoenix palms Donald Arrowsmith photographed in Hastings in 1962. Unfortunately, it was discovered that by 2005 only one out of five palms remained. Development work and the siting of a new war memorial statue in the cenotaph area explained the removals. We’ll now move to the case of Gisborne where we’ll see a new reason for removal: the more recent emergence of a ‘pest plant’ status for the Phoenix palm. This development originated in Auckland, ironically the epicentre of the popularity of the Phoenix palm in New Zealand. First it is useful to begin by reconsidering the two photos that Donald Arrowsmith took in Gisborne in 1962:

227 Beside the River, Gisborne

229, Beside the River, Gisborne

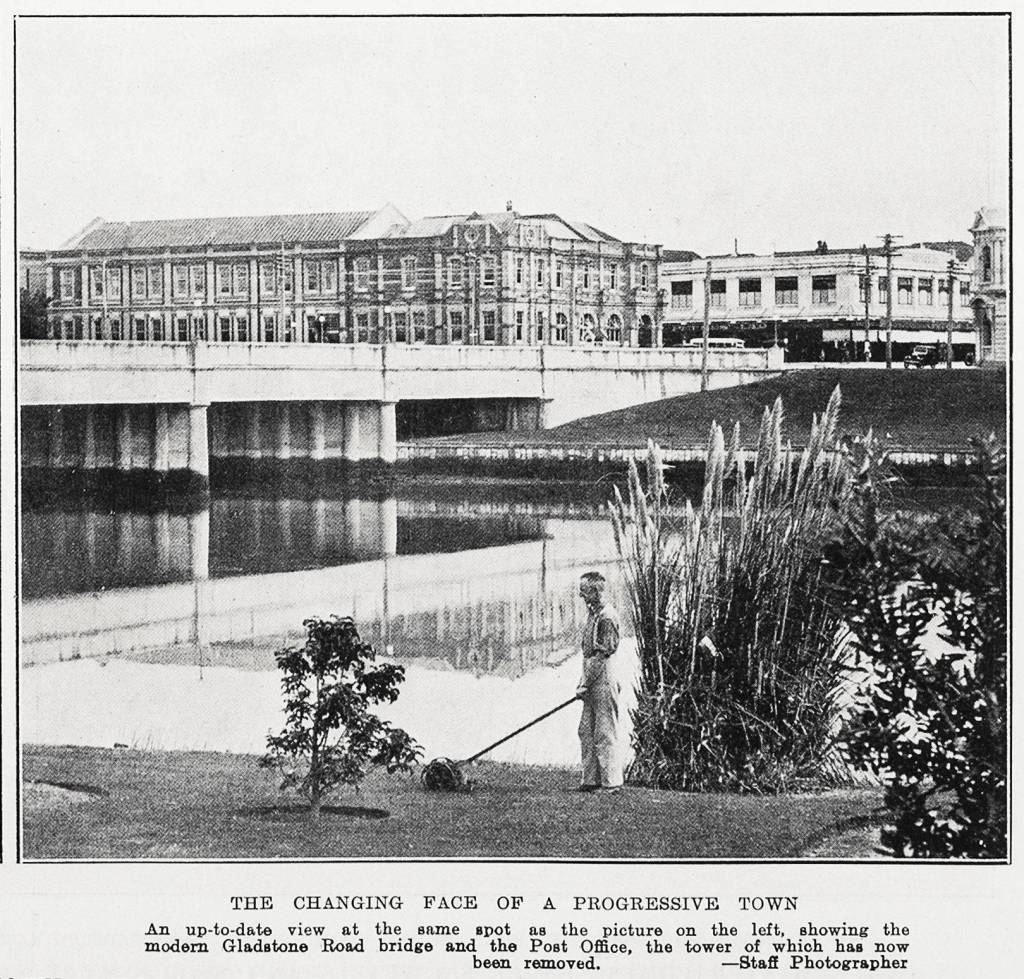

Photo 227 looks up the Turanganui River to the rail bridge, and photo 229 looks across the river which is spanned by the Gladstone Road Bridge (just past the rail bridge). The bridge, which has a category 2 Historic Place listing, was opened on 26 March 1925. Its reinforced concrete construction was at the time an ‘advanced technology’, taken to indicate that Gisborne was a progressive town. Functionally, it linked Gisborne’s town centre with the main highway north, also occupying a scenic site. Despite the latter, historic photos from the early 1920s show that the surrounding landscape was mostly barren:

Source: Gladstone Road Bridge and Wharf, Gisborne, undated photograph, 41330 Tairawhiti Museum

This undated photo looks to have been taken not long after the bridge’s opening, showing in the background a very bare Kaiti Hill and what look to be pines and gums in the mid-distance. The bareness of the riverbank lasted at least to 1934:

Source: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19340523-40-05

The planting that has clearly just begun on the eastern side of the river was soon to be joined by planting on the other side. A lot of this was due to the actions of the Gisborne District Beautifying Association, which by 1935 had future plans reported to include the use of ‘One hundred Phoenix palms’.1 Within a decade some of these one hundred palms2 were planted along the bare riverbank, significantly transforming it:

Source: Turanganui River, Gisborne. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1799-0055

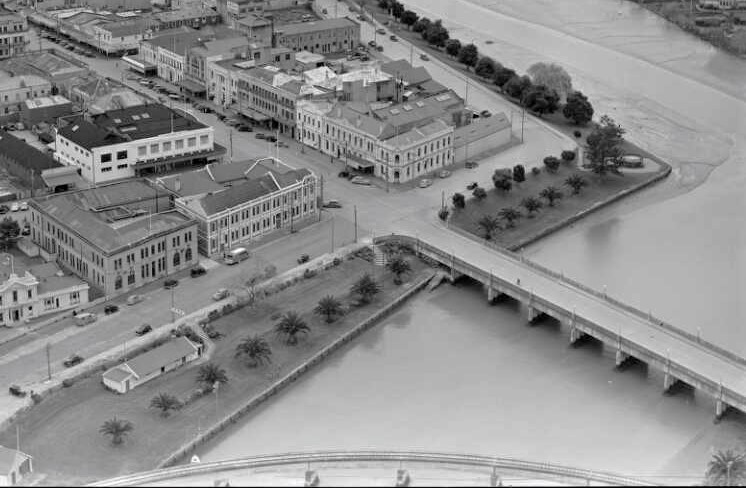

A photo from 29 August 1949 shows better the extent of this significant transformation of the riverbank:

Source: Gisborne. Whites Aviation Collection. Ref: WA-21756-G. Alexander Turnbull Library. /records/22849843

Looking closely at the bottom right corner one palm of the cluster between the two bridges on the east side of the river can be seen. Newspaper reports suggest that all of the riverside palms were planted about the same time, that is between 1934 to 1936.3 Some recent images give a good feel for what these palms look like at 90 years old:

Source: Gisborne District Council Facebook page, 2024.

Source: Google Maps, Street View, May 2019

The Google Street View image is taken a little back from Donald Arrowsmith’s photo 229, but it is more or less the same location. From it we can see that across the river the group of Phoenix palms included in Donald’s photo have disappeared.

The Consequences of ‘Pest Plant’ Classification

It turns out that this disappearance was part of a significant removal of Phoenix palms on the east side of the river. A map will contextualise this, but before this we need to briefly describe the history of the ‘Pest Plant’ classification of Phoenix palms.

The move to pest plant classification occurred in Auckland as early as 2004.4 Influenced by a relatively small number of people pushing their argument, the Auckland Regional Council began expressing concern about the naturalisation of Phoenix palms in Auckland ecosystems, including mangrove landscapes. Ultimately, despite opposition by local gardeners and horticulturalists,5 by 2010 a strict regional pest management plan prohibited the distribution and sale of Phoenix palms within the Auckland region. This devaluation of the palm was reinforced by comments that the palm crowns harboured rats, and that spikes on young palm fronds led to piercing injuries. News of this pest plant classification spread throughout the North Island, including to Gisborne: by 2018 Phoenix canariensis was included in a list of about 30 trees in an ‘Unsuitable Tree Schedule’ within Gisborne’s Street Trees and Gardens Plan. The problems with the palm were succinctly described as ‘spiny fronds, prolific seeding, weedy’. It was these factors that led to the palm being placed in the Regional Pest Management Plan, having exactly the same implications as the Auckland strategy: Phoenix palms were not to be planted, and if already existing the preference was for their removal.

The effects of Gisborne District Council following the precedent set in Auckland, was set in train by another development about this time: the Inner Harbour Upgrade Project. A map is useful to show where this project was centred:

The Inner Harbour Upgrade Project covers locations 2 and 3 on the map. We have already noted that the palms at location 2 – Donald’s photo 229 – had disappeared before 2019, but the upgrade project explains why and also indicates the extent of the Phoenix palm removal. The first removals were 3 palms removed in December 2016. These were at Crawford Road situated next to The Works restaurant, with the Mayor at the time (Meng Foon) commenting, ‘We’ve received a lot of complaints about pests and hazardous branches from these trees from businesses nearby’.6 From Google Map images these palms appear to have been planted after the original 1934-1936 Phoenix palm planting spree. However, only 100 metres away at The Esplanade were Phoenix palms definitely planted in 1934.7 Some ‘before and after’ photos best show what happened here:

The left image is a Google Map street view from August 2017, whereas the right is from August 2018 (a stump can still be seen). The Gisborne Herald Facebook page included a video of the tree removal, showing both the size of the palms and how they were removed:

Five palms were removed in this manner on May 16 2018. The larger number of palms at location 2 were not removed until after August 2018, but do not appear to have received any similar media commentary (perhaps it was no longer newsworthy by this time).

Referring back to the map above, if we now add what happened at location 4 we can see that the Reads Quay row of Phoenix – location 1 – now appear caught in a kind of ‘pincer movement’. A media article from 2023 reports that ‘the last of around 50 Phoenix palm trees were removed yesterday morning as part of the Waikanae Stream Renovation Project’.8 Waikanae Stream is location 4 on the map. These palms do not appear to have been part of the 1934-1936 Phoenix palm planting. Irrespectively, their removal clearly shows that the Gisborne District Council was putting its own pest management policy into effect.

Perhaps what saved the Reads Quay row from removal was both their size and location. The very fact that the Gisborne District Council used photos of this location in their public imagery (see above), with the palms standing monumental, shows just how much of a taken-for-granted part of the riverside scenery they had become. There are plenty of historic photos which show this, including this resonant image:

Source: ‘Cook Bi-centennial Street Parade’, Derek Allan, 9 Oct 1969, Photo 47952 Tairawhiti Museum

This shows some of the Reads Quay palms just 7 years after Donald Arrowsmith photographed them, of course without the crowd marking the Cook Bi-centennial. It is a moot point whether the row of Phoenix palms will still be there at the Cook Tri-centennial in 2069. Their lifespan certainly means they would live that long, but as we have seen above it is the social judgements around Phoenix palms that mainly seems to limit their longevity (at least in New Zealand).

A Positive Note

Following what happened to the Phoenix palms that serendipitously appeared in Donald Arrowsmith’s photos we have undoubtedly seen a great deal of disappearance. Perhaps that is partly to be expected, for as Elkin powerfully states, ‘[Humans] plant trees to stimulate meaning, expression, and awareness, provoking poetry, art, and belief. We plant trees by necessity, to secure food, shelter, comfort, and fuel. But there is more to this. Humans also plant trees because we are very good at taking them down’.9

We don’t need to track through them, but to end on a positive note it should be emphasised that some of the Arrowsmith Palms remain in their entirety. These are, in the order in which we encountered them: Albert Park, Auckland; Auckland Zoo; Government Gardens, Rotorua; Pukekura Park, New Plymouth; and Roulston Park, Pukekohe. I happened to be in Albert Park in late 2024, and whereas I didn’t intend to take a photo where Donald took his, this final photo is very close to the location of the fountain in his photo 168. I think it shows that despite the spread of the pest plant classification the palms still have their place in the New Zealand landscape:

- ‘Beautifying Gisborne’, Gisborne Times, 2 July 1935, p. 5 ↩︎

- Not all of the 100 palms were planted along the riverbank. Other likely planting places, many of which can still be seen today, include the Gisborne Botanic Gardens (about 20 palms), along Awapuni Road (about 15 palms), and the Gisborne Racecourse (about 15 palms). ↩︎

- Newspaper reports confirm this, for example, see: ‘Borough Affairs’, Poverty Bay Herald, 10 October, 1934, p. 8; ‘Planting of Trees’. Poverty Bay Herald, 3 July 1935, p. 13; ‘Untitled’, Poverty Bay Herald, 23 February 1937, p. 4. ↩︎

- See ‘New research rings biosecurity alarm bells’ Press release from Auckland Regional Council, 19 October, 2004, available on Scoop: https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/AK0410/S00144/new-research-rings-biosecurity-alarm-bells.htm. ↩︎

- See W. Thompson, ‘Gardeners to Fight ARC Palm Ban’, New Zealand Herald, 12 Jan, 2006. ↩︎

- ‘Pest Attracting Trees to be Removed’, Scoop, 21 December, 2016. ↩︎

- ‘Borough Affairs’, Poverty Bay Herald, 10 October, 1934, p. 8. ↩︎

- ‘Phoenix Palms Removed’, The Gisborne Herald, 18 March 2023. ↩︎

- Elkin, R.S. (2022) Plant Life: The Entangled Politics of Afforestation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 1. ↩︎