Trees have been used as memorials for centuries. It is no surprise then that with the end of both 20th century world wars service people were commemorated by the planting of trees, either singly or in groups. The latter were often planted by roadsides and became known as ‘memorial avenues’. Here we’ll visit a memorial avenue in the Wairarapa district known as either Maungaraki or Gladstone.

In New Zealand, many of the better-known memorial avenues were established just after World War One, often being called ‘peace’ or ‘victory’ trees1. These may have had individuals associated with them, that is. plaques with the names of individual service people were sometimes affixed to trees, but practices of memorialisation varied.

Scholarship on this topic tells us something interesting. As a form of memorial often based in a desire to recognise and remember those who lost their lives, memorial avenues were obviously based in a strong emotional dynamic. Despite this, many trees planted in such avenues quickly disappeared. A good example is provided by Eric Pawson in his study of the ‘memorial oaks of North Otago’. These were first planted in 1919 close to Oamaru, initially being a well-supported and extensive means to memorialise North Otago’s First World War fallen soldiers. However, by 1992 over one third of the trees had disappeared.2 Even as early as the 1920s many of the roadside-planted oaks were lost to road-widening, or were severely pruned to enable the introduction of electric power lines. As Pawson notes, by the mid-1950s many local residents driving in the region no longer knew the story behind the oak trees bordering the roadway.

Knowledge Helps With Observation

I was aware of the existence of memorial avenues, and the tendency for them to partly fall from memory, when in June 2025 I spent a week in the Wairarapa (see the earlier blogpost Some Rural Pines From a Wairarapa Trip). Fortuitously, this led to the observation at heart of this current blog.

On a clear winter’s day a friend and I drove the back road from Martinborough to Masterton. This was the first time I had been on the road, so didn’t know what features were in the various locations. It was no surprise though to turn a bend and come upon this sight:

It was clearly a war memorial, something commonly seen in almost all small New Zealand towns,3 so on this first trip I didn’t stop. However, just 400 metres northward I saw something that led to a strong ‘note to self’: google this when you get home. Here are two photos showing what was of interest:

The top photo shows the view across the Tauera River, where there is a double row of trees. Getting closer, as in the second photo, a decent guess can be made that they look like scarlet pin oaks (Quercus plalustris). There is though nothing to indicate any memorial function for this double row. But informed by my awareness of memorial avenues, bolstered by the obvious proximity of the row of trees to the war memorial cenotaph, there was definitely something to pursue here. It took less than a minute of googling to find this information:

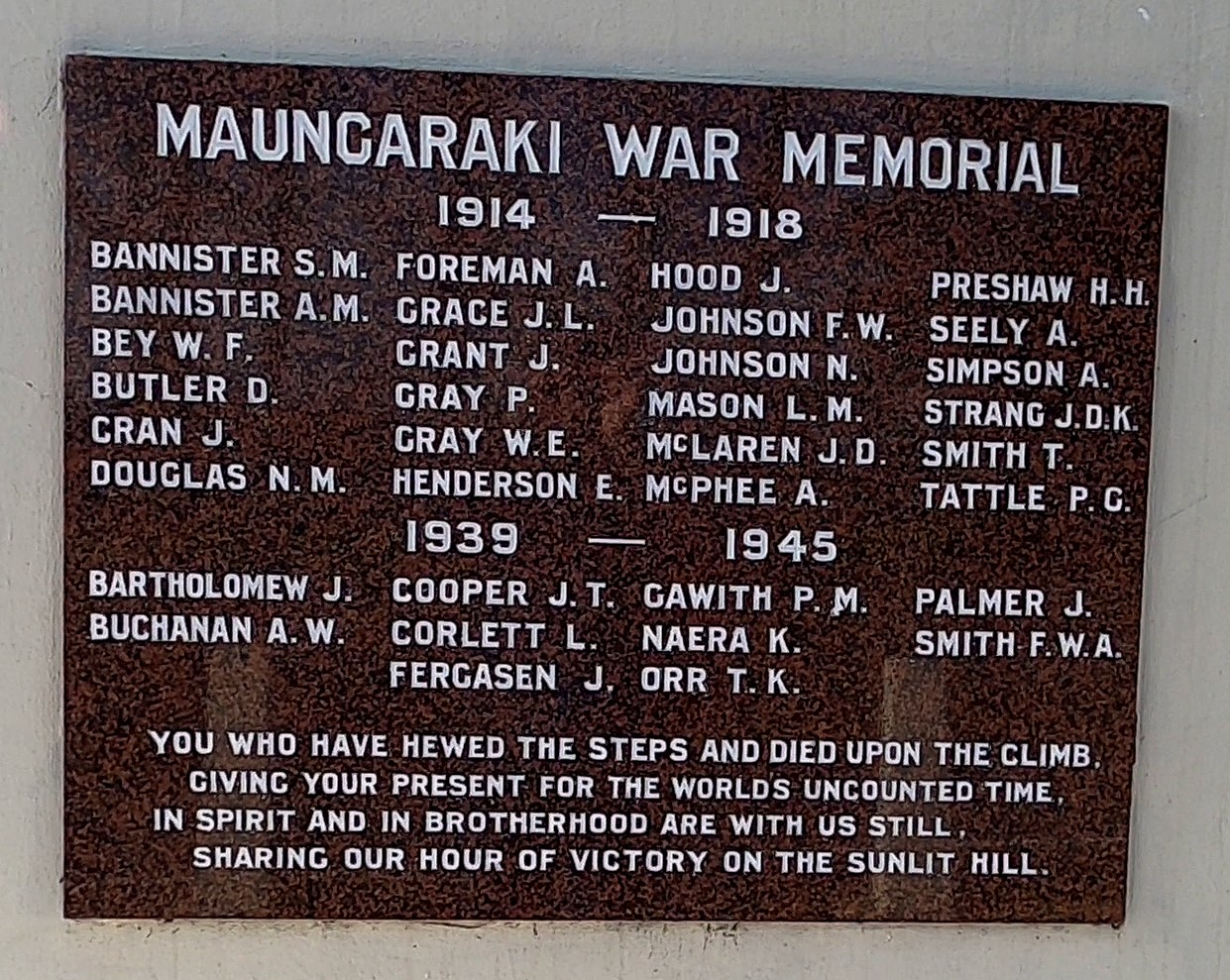

This came from a Ministry for Culture and Heritage entry providing a paragraph on the connection between the oak trees and the cenotaph. In brief, Following World War II effort was put into an appropriate memorial for those from the Maungaraki District (centred on Gladstone, Wairarapa) who lost their lives in action during both WWI and WWII. A new bridge was planned to span the Tauera River and it was decided to design a memorial on either side of the bridge. On the north side 36 pin oaks were planted, and on the south side the memorial plinth was erected. Each of the 36 oaks, in a double avenue, represents a local who lost their life, with two additional trees planted as ‘guardians’ (the names are listed on the cenotaph). There is no record available that detais when the trees were planted, but it looks likely to be about 1950.

The trees do not have plaques, nor is there any signpost or information board with them, so most people driving past do not know their significance. A stop has to be made at the War Memorial plinth to find any information:

This sign is next to the cenotaph which lists the names of the soldiers:

This information may lead some people to park their car and walk back to the memorial avenue of oaks. But perhaps just as with Pawson’s comment about the North Otago memorial plantings, the vast majority of people will pass through with no idea of the row of trees’ significance. Scarlet oaks are not particularly unusual in New Zealand, but armed with the knowledge about the memorial trees I returned to the site, taking the photos seen here which help give a better indication of the scale and visual impact:

Using the Trees: An Extra Insight

I’ve never been to an Anzac memorial event, so my interest in the trees in memorial avenues came from the arboreal angle and not any specific military or personal interest. But in doing a little reading to find information on the Maungaraki avenue I chanced upon a section in Pat White’s book How the Land Lies: Of Longing and Belonging.4 Pat lives in Gladstone, and has family connections in the area, including a great uncle called Jack Dunn, who was killed at Gallipoli. There is a backstory to his service there, but a lengthy quote from White’s book nicely illustrates how an avenue of trees can actually be used in memorial work:

It was Anzac Day. A group of us had decided on the spur of the moment to meet at our local war memorial plaque. Before dawn, I went with Catherine to joine some friends down at the avenue of Memorial Oaks … We walked in the dark through the thirty-six Memorial Oaks, while names were read, to where the cenotaph stands with those names inscribed. Those are the local men who went from this district during two wars to fight and be killed. At the cenotaph, while candles burned in the half light, poppies and wreaths were laid, poems, including McCrae’s In Flanders Fields, were read, a hymn sung, and a recording of the Last Post was played. A minute’s silence was punctuated by the call of plovers. Ducks quacked as they flew off across the paddocks that surrounded us and somewhere magpies yodelled their chorus. As the dozen or so of us who had, on the spur of the moment, gathered, were now preparing to leave, the eastern sky bled red into colours of daylight. To the west standing silent and cobalt blue – the Tararuas, our horizon to this place, and sentinel to a small act of collective memory. (pp 140-141)

Regardless of your stance towards war memorialisation, the double row of trees clearly contributed to the significance of this personal and collective act of memory. Signposts could be erected to indicate their history and significance; on the other hand, perhaps it is fitting that knowledge of why they were planted remains with those from the region able to make lively the growth of the pin oaks in this isolated rural location.

- See I. Bargas & T. Shoebridge, New Zealand’s First World War Heritage, Auckland: Exisle Publishing. Several examples are given in the book, but the largest has to be Fairlie’s Peace Avenue where 500 trees were planted. Also see J.-A. Morgan, 2008, ‘Arboreal Eloquence: Trees and Commemoration’, Unpublished PhD. University of Canterbury ↩︎

- E. Pawson, ‘The Memorial Oaks of North Otago: A Commemorative Landscape,’ in G. Kearsley & B. Fitzharris, eds. Glimpses of a Gaian World: Essays in Honour of Peter Holland. Dunedin: School of Social Sciences, University of Otago, 115-131 (2004). This disappearance is not an isolated case. Seventeen memorial trees were planted in Manurewa in 1917, but over the years many died or were removed, and ultimately by the 1950s none remained. A new ‘peace tree’ was planted in 2015 to replace the lost memorial trees. See Ministry for Culture and Heritage, Manurewa Memorial Trees. ↩︎

- For the key work on this topic see J. Philips, 2016,To the Memory: New Zealand’s War Memorials. Nelson: Potton & Burton. ↩︎

- See the chapter ‘Tararuas as Gallipoli: Suite’,Pat White, 2010, Wellington: VIctoria University of Wellington Press. ↩︎

Leave a comment